How VCs Make Money?

Why 90% of Startups Fail but VCs Still Get Rich — The Shocking Math Behind Venture Capital Profits!

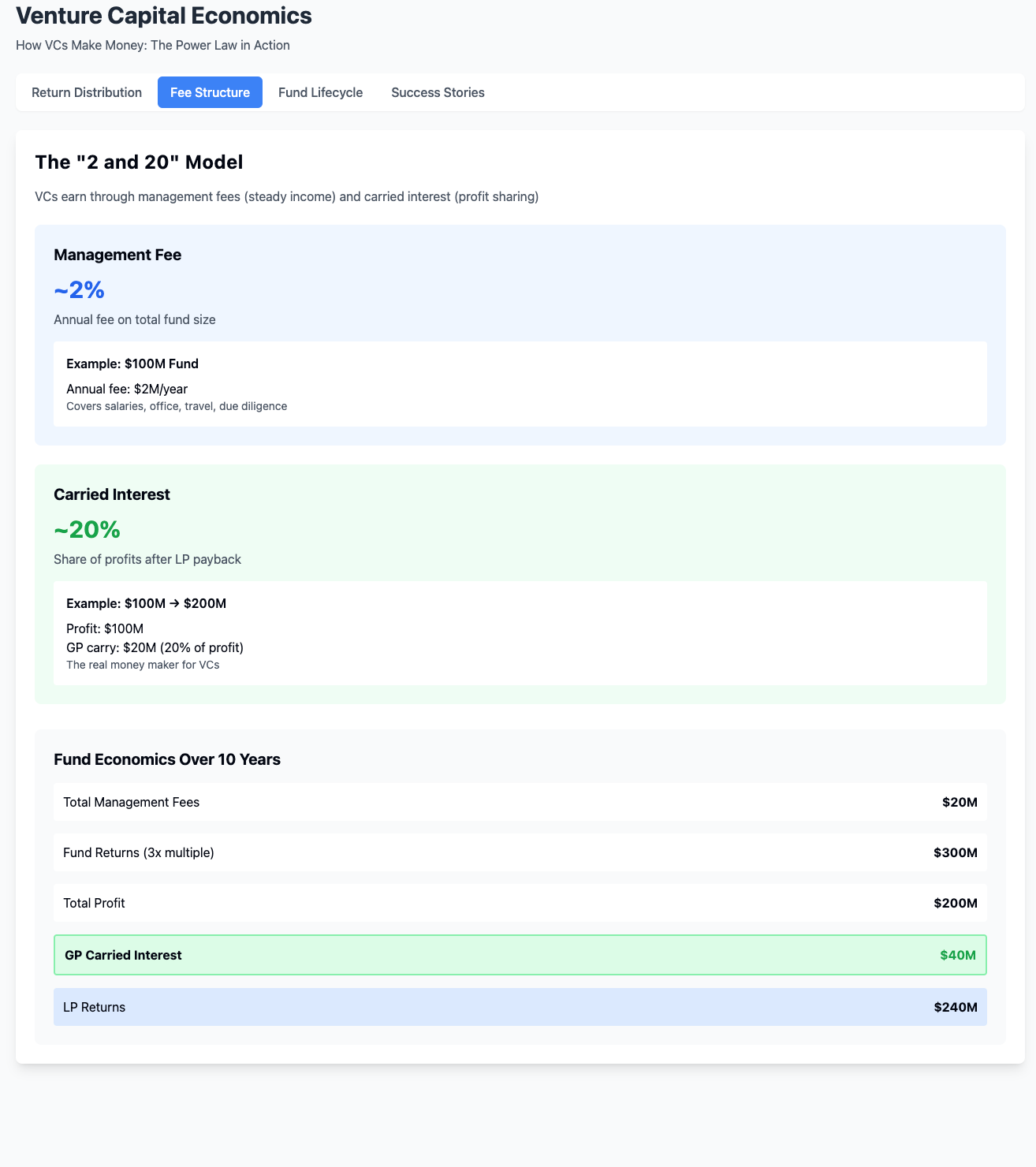

Venture capital (VC) is like a high-stakes lottery or orchard – most seeds never sprout, but one giant tree can make the whole harvest worth it. VCs raise a big pool of money from pension funds, endowments and rich people (called limited partners, or LPs) and use it to invest in many startups. The VC firm (the general partner, or GP) charges fees for managing the fund and takes a cut of any profits. In simple terms: a VC firm charges roughly 2% of the fund each year as a management fee and then keeps about 20% of the overall profits (called carried interest) once the investors get their money back. Most funds last around 7–10 years (often extendable), so during that time the GP might take in fees on multiple funds.

Management fees: Typically ~2% of committed capital per year. On a $100M fund, that’s ~$2M/year to cover salaries, office rent, travel and due diligence. (Fees often taper to ~1% in later years.)

Carried interest (carry): After the fund sells or exits its investments, the GP keeps about 20% of the profits. For example, if a $100M fund invests and eventually returns $200M, the $100M gain yields a $20M fee to the GP (20% of $100M). This profit share is the GP’s big payday, far larger than the fees.

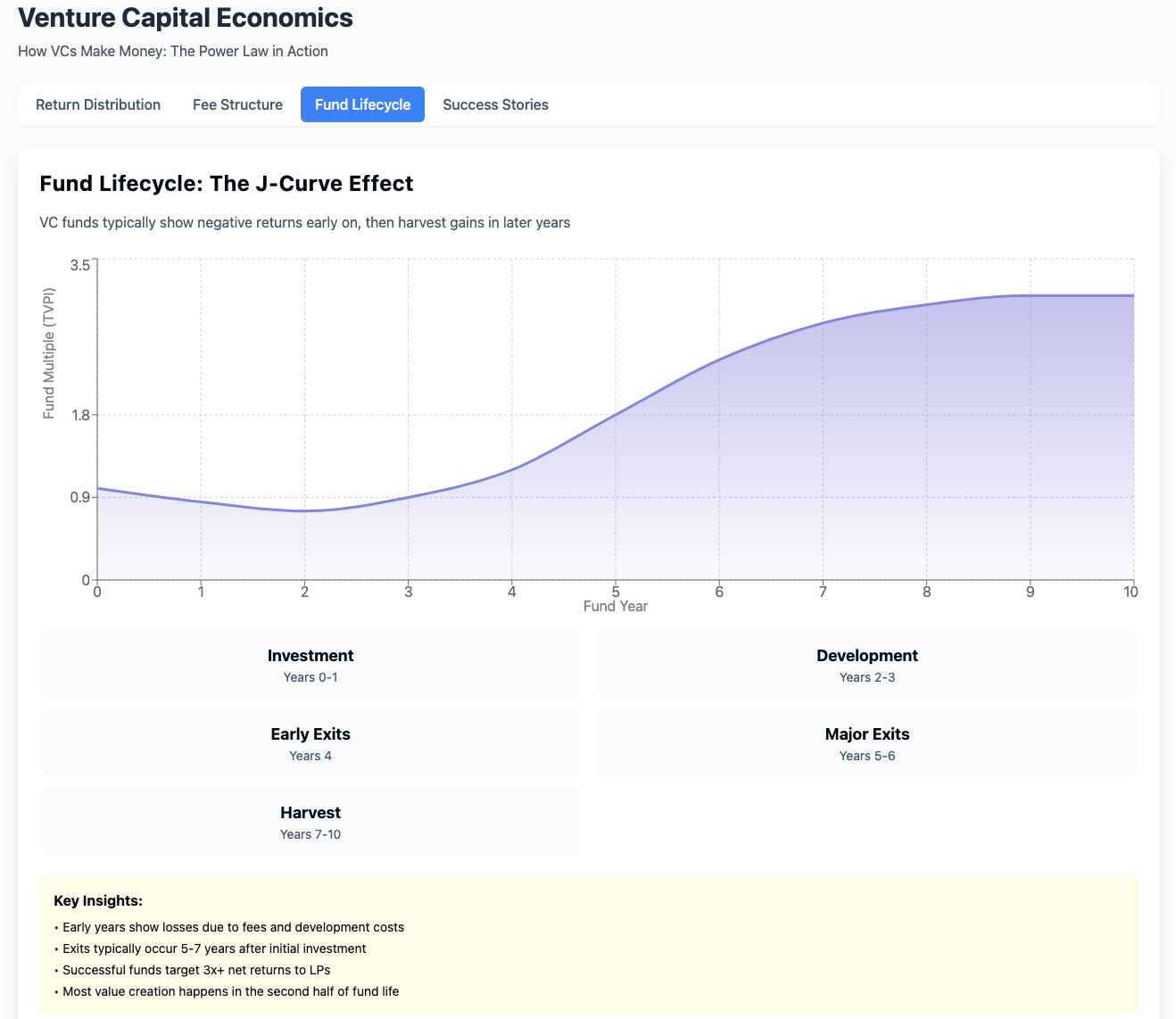

Fund life: A fund’s life is typically ~10 years. Early on there’s a “J-curve” where fees and costs make the fund look underwater. Only after several years do exits happen and TVPI (total value to paid-in) rises above 1.0.

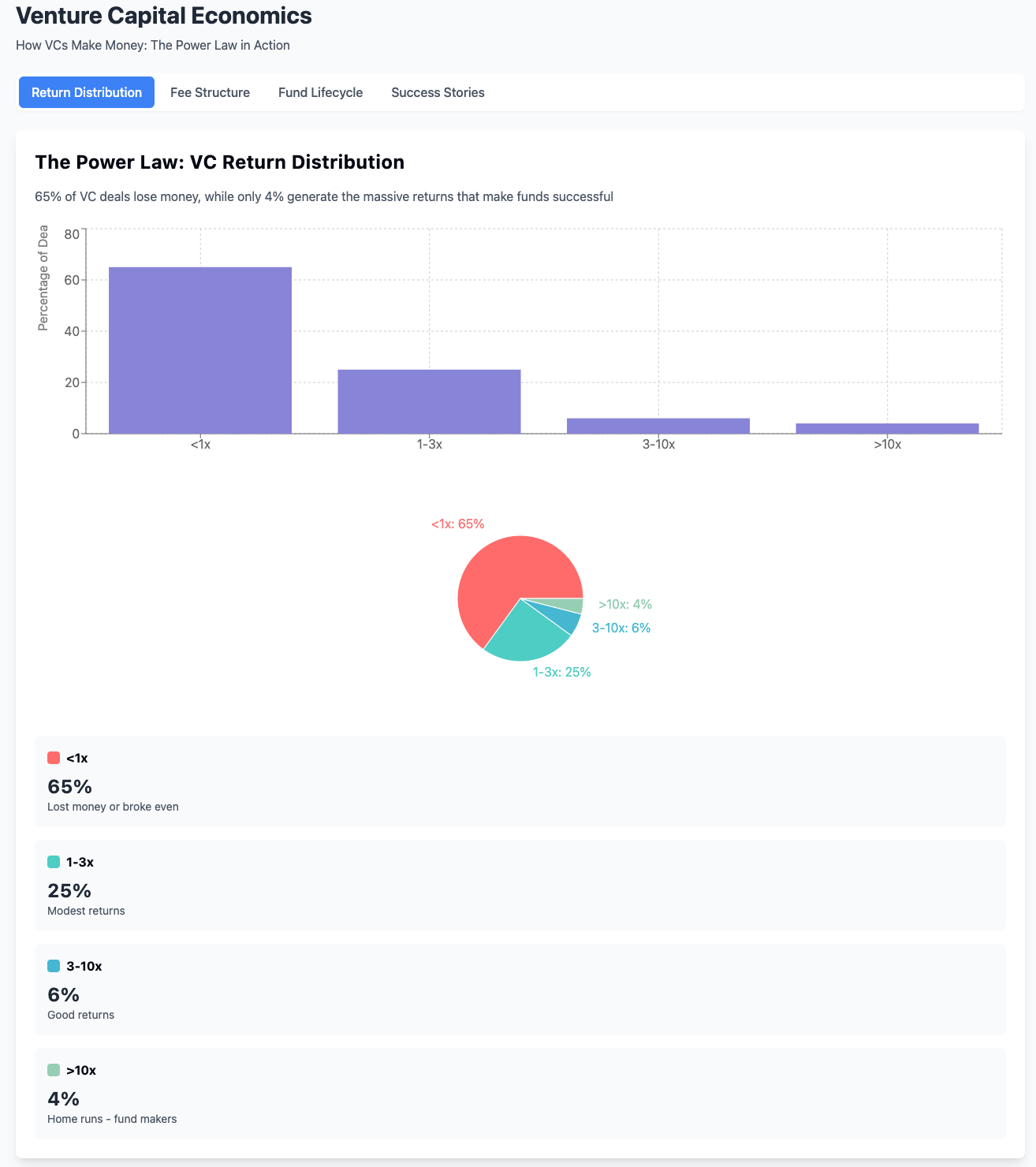

In practice, VC partners live off the fees while they hunt for a few “home run” deals. They hope to double or triple (or much more!) the money for their investors, because only a few winners generate almost all the returns. This power-law pattern means a VC often needs 1–3 huge wins to justify an entire fund’s performance. As one analysis puts it, most VC-backed rounds don’t even return the original cash: about 65% of deals yielded less than 1× (i.e. returned the LP’s capital or less) and only 4% of deals returned more than 10×. In other words, imagine 100 lottery tickets: perhaps 65 lose, 31 win a little, and only 4 pay off big. To make a fund work, one or two of those big winners must make up for the many misses. Top-performing funds often have several 10× or 50× hits, whereas a median fund usually has none.

Because of this “hits-driven” math, VCs diversify – they back a portfolio of startups (often dozens) knowing most will fail or underperform. It’s like planting many seeds and hoping a few grow into giant trees. If a fund has 30 investments of $3M each, even one 50× returner on $3M ($150M) only covers half the fund (and that ignores fees). Venture funds thus typically aim to return at least ~3× net of fees (roughly 3.5× gross) overall to be considered successful. In total, older vintages of funds often show median multiples of ~2–3×, meaning LPs ultimately double or triple their money after a decade.

VCs explain this with an analogy: only a few company successes compensate for many failures. Picture a baseball lineup: you need a couple of home run hitters to win the game, not just singles. Or think of a miner panning for gold – sifting through lots of sand to find a nugget. This is why VCs talk about the “power law” of returns: a tiny fraction of investments create most of the rewards.

The VC Deal Process

A typical VC fund goes through a lifecycle: it raises money, invests, then harvests. First, the GP collects commitments from LPs (e.g. pension funds, endowments, wealthy families). This pool – say $100M – is the fund’s capital. The GP will spend a few years making investments, usually in stages (Seed, Series A, B, etc.). They might invest $5–10M in each startup, spreading risk across 15–30 companies. During these years, the firm charges a management fee to cover staff and due diligence.

As startups grow and raise new rounds, each round issues new shares. This causes dilution: every existing owner’s percentage stake shrinks as more shares are created. For example, if you own 10% of a company after the first round, a larger Series B might cut you to 5%. Founders and early VCs accept dilution as long as the company’s overall value is skyrocketing. In plain terms: “Your slice of the pie might get thinner, but the pie itself should be much bigger.” (Learn more: dilution simply means new investors bought in, reducing your ownership share.)

Eventually, one of two things must happen: exit events. The startups either get acquired by another company, or they go public (IPO). These are the “harvest” moments when LPs and the VC can cash out. If a startup never exits and remains private for the life of the fund, the fund may end up writing it off or valuing it at market cap (which can be illiquid).

✶ Example: Think of a fund like an orchard. VCs plant (invest) lots of saplings (startups). Over years they water them (provide advice, follow-on funding). After ~5–10 years, some saplings bear fruit (exit) – like an apple (IPO) or orange (acquisition). Each fruit is sold at market and the proceeds go to LPs and the VC. If a tree dies (startup fails), nothing is harvested.

Fees, Carry, and Returns (2‑and‑20)

Most VC funds use the “2-and-20” model (though exact numbers can vary). In a bullet list:

Management fee (~2%): Charged annually on the total fund size. On $100M, that’s ~$2M per year. Early in the fund’s life the fee is often highest (2%), and it may drop to 1% in later years. These fees pay the VC team’s salaries, office costs, travel, legal, and audit. Think of it as the salary for managing the fund.

Carried interest (usually 20%): The GP’s share of profits. After the fund returns the original capital to LPs, the GP keeps 20% of any additional gains. For example, if a fund invests $100M and ultimately gets back $200M, the $100M profit yields $20M carry for the GP. (The remaining $80M profit goes to the LPs.) Some top firms negotiate higher carry (e.g. 25-30%), but 20% is common.

So how does a VC make real money? Over the fund’s life, they collect millions in fees (enough to pay salaries) – but that alone usually doesn’t yield a huge profit. The real windfall comes from carried interest on the big exits. If a fund has a mega-success, the 20% carry on that one deal can dwarf all the fees collected. That’s why VCs cheer big wins. (If a fund fails to make profits, the GP might still get fees, but they won’t get much or any carry. In the worst case both LPs and GPs lose money.)

Portfolio Strategy & Power Law

VCs invest in many companies knowing most will tank or just limp along. They rely on the few big successes to carry the fund. Data illustrates this clearly:

High failure rate: Roughly two-thirds of VC investments don’t even return the principal. As noted above, 65% of startup rounds returned under 1× (i.e. investors got back less or none) in one study.

Tiny fraction of outsized hits: Only a handful of startups return more than 10×. One analysis found just 4% of deals returned over 10×. In practice, those rare 10x–100x winners supply the lion’s share of a fund’s gains.

Fund targets: Because of this, a successful VC fund usually expects to return at least ~3× (net) overall. If a fund doesn’t reach ~2–3×, LPs often consider it underperforming.

In simple terms, imagine you have 10 lottery tickets at $1 each. In a regular lottery most tickets win nothing; one might win $50. Even though 9 tickets lost, that one winner gave you $50, which more than covers the $10 total spent. Similarly, a VC needs that one big hit to justify funding dozens of startups. If none hit the jackpot, the fund can fail.

Because of this pattern, VCs diversify their bets. A typical fund might invest in 20–30 companies, or even more. They will often reserve capital to follow-on pro rata in winners so as not to lose too much ownership. (By contrast, angel investors may invest in just a few companies.) In sum, the VC plays the odds: by spreading bets, they increase the chance of catching the rare unicorn.

Exits: Harvest Time

A startup investment only pays off when there’s an exit. VC-backed companies usually exit in two ways:

Acquisition (M&A): Another company buys the startup outright or a majority stake. Many exits are acquisitions by larger tech firms.

Initial Public Offering (IPO): The startup lists on a stock exchange, allowing LPs and GPs to sell shares on the public market.

It’s important to note that exits take time. Venture money is locked up for years. On average, VC-backed companies take 5–7 years to reach an exit. For acquisitions, one study shows the average time to exit is about 6.3 years from first financing (median ~5.4 years). IPO exits have a similar multi-year timeframe – roughly 5–6 years on average in recent data. This means a VC usually waits half a decade (or more) before getting any big paydays.

In practice, this long wait contributes to the “J-curve” effect mentioned earlier. Early on, a VC fund shows negative returns (due to fees and company development costs). Only after a wave of exits – often near the fund’s later years – do LPs start seeing cash distributions. Until that harvest, the GP is essentially managing risk without payout.

Key point: Because exits are the only way to turn equity into cash, many startups stay private much longer than before. Today it’s common for companies to go public only after many funding rounds, and in the meantime VCs hold shares on paper. If market conditions are poor, exits can dry up; in 2022–23 IPO and M&A activity slowed dramatically, delaying returns for many funds. LPs know a VC fund is a long bet on the future.

Examples from the Field

Nothing illustrates “how VCs make money” better than real success (and failure) stories:

Sequoia & WhatsApp: Sequoia Capital invested about $60M total into WhatsApp between 2009–2013. When Facebook bought WhatsApp in 2014, Sequoia got roughly 20% of the sale proceeds – about $3 billion. That’s roughly a 50× return on Sequoia’s investment. One deal turned pocket change into a fortune for the fund.

Accel & Facebook: In 2005, Accel Partners put $12.7M into Facebook for ~11% equity. By 2012 Facebook’s IPO valued the company enormously; Accel sold some shares to pay back its fund, fetching about $500M in cash, and still held ~8% of Facebook worth another ~$3B. In total that $12.7M grew to ~$3.5B – over a 270× gain. This one investment essentially “paid off” the entire $440M fund and then some.

SoftBank & Alibaba: In 2000, Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank invested $20M in Jack Ma’s tiny startup Alibaba. When Alibaba IPO’d in 2014, SoftBank owned ~24% of the company. (Alibaba’s IPO was ~$25B, valuing Alibaba far over $150B at peak). SoftBank’s initial $20M stake became tens of billions of dollars (a ~1500× return) by 2014. (SoftBank later sold down its stake.) This is one of the all-time VC-type windfalls.

SoftBank Vision Fund: Contrast that with a cautionary tale. In 2017 SoftBank raised the $100B Vision Fund, making huge bets on tech (Uber, WeWork, etc.). By 2020 the Vision Fund had suffered spectacular losses – notably WeWork’s IPO flop – and lost about $18 billion in one year. That wiped out gains and hammered LP confidence. Here, lack of exits (or bad exit valuations) meant investors lost money, and SoftBank’s promised vision didn’t pan out (leading them to shelve raising another big outside fund).

Other tales: There are countless more: Benchmark’s $6.7M bet on eBay (17× return), Kleiner’s early Google shares (hundreds×), New Enterprise Associates in 10Gen (MongoDB’s IPO), and so on. Conversely, many funds have investments like WeWork or Theranos that go to zero. The lesson: one big hit can overshadow many misses, and one big miss can drag down all your gains.

These stories show how VC profits are wildly skewed. A single home-run deal (WhatsApp, Facebook, Alibaba) can bankroll a fund, while just a couple of failures (like a big down round or collapse) can erase years of value. It also shows why VCs cling to the long tail of many investments: if one skyrocket company is in the mix, it makes all the difference.

Pulling Back the Curtain: Key Takeaways

Two revenue streams: VCs earn management fees (small, steady) and carried interest (big, but only on winners). Fees cover the business; carry is the jackpot.

Portfolio approach: Expect many failures and few wins. Data show 65% of startup deals lose money and only ~4% pay off big. The fund’s overall return hinges on capturing the rare 10×–100× outliers.

Long horizon: VC is not a quick flip. Exits typically take 5–7 years. Patience is required – both for GPs and LPs. The “harvest season” often comes in a fund’s latter half.

Fund multiples: Historically, median VC funds have ended up around 2–3× money (older vintages). But top-quartile funds can be 4–5× or more, while the worst may not return the full capital. VCs generally aim for ~3× net (3.5× gross) to justify the risk.

Dilution: Every new funding round dilutes earlier shareholders, but ideally each round grows the company’s value more. VC ownership percentages shrink over time, but what matters is the value of that stake. Entrepreneurs and VCs expect dilution in exchange for growth capital.

Examples are extreme: Remember Sequoia’s 50× WhatsApp win or Accel’s ~270× Facebook win. These outsized returns illustrate why VCs chase fast-growing companies. But also recall SoftBank’s multibillion-dollar losses – even giant funds can struggle when exits go wrong.

For aspiring founders and new investors, the VC model boils down to this: VCs are agents of high risk, high reward. They get paid (fees) to put on the show, but they win big only when their investment performers hit the jackpot. Understanding these mechanics can help entrepreneurs negotiate (knowing VCs need big upside) and appreciate why VCs care so much about growth, market size, and eventual exit strategy.

In sum, venture capitalists “make money” by planting many seeds of capital, watering the most promising ones, and selling the fruits in a few bountiful harvests. With luck and skill, a few blockbuster startups will cover the costs of all the others, yielding handsome profits (and carried interest) for the firm and its investors.

💰👍🏻